On September 18, 2021, The Carolina Lightnin’ will celebrate the 40th anniversary of their incredible expansion-year championship victory.

CHARLOTTE—There’s a movie script waiting to be written about Charlotte’s first-ever professional soccer team.

The Carolina Lightnin’ debuted in 1981 and won a championship in its very first season. Few sports franchises can make such a claim.

The first professional team in the Carolinas played in front of record-breaking crowds, who were enticed by a winning team and an ownership group that became notorious for match day gimmicks. They gave away cars and airplanes at half time, and once hosted a Beach Boys concert after the final whistle.

Among their motley crew of players was an iconic World Cup-winning defender whose statue stands outside the gates of Wembley Stadium. Meanwhile, the MVP and top scorer of the Championship-winning season initially drove the team bus, and only made his way onto the field as a last resort. Another of their players was struck by a bolt of lightning during a game.

Yes, you read that correctly: the Lightnin’ were struck by lightning.

The tale of Charlotte’s first pro soccer team is so extraordinary and improbable that the movie script would sound like a work of fiction.

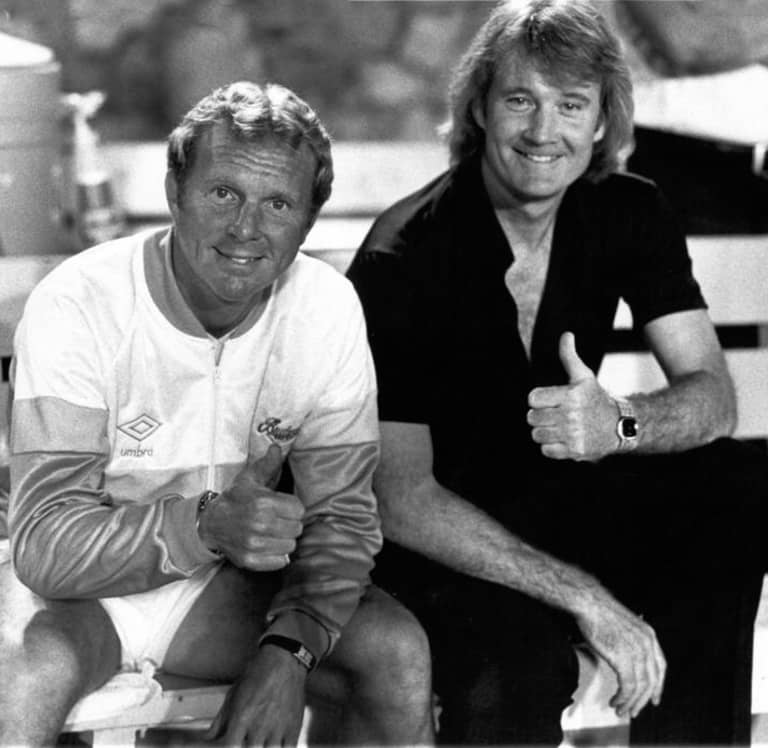

“It’s such a wonderful story,” says former England and Manchester City star Rodney Marsh, who coached the Lightnin’ during their fairytale campaign. “It was a perfect storm of coincidences, happening all in one magical season!”

In April 1981, the Lightnin’ franchise embarked on their debut campaign in the second-tier American Soccer League. The team earned its name after a contest in the Charlotte Observer garnered over 7,000 entries, and it played its matches at American Legion Memorial Stadium—now home to the Charlotte Independence.At the time of their launch, Charlotte’s ability to support a professional sports team was in question. The Carolina Cougars of the American Basketball Association and the Charlotte Hornets of the World Football League had both become defunct in the mid-1970s, when their respective leagues folded.

The Lightnin’, however, arrived on the scene when American interest in the beautiful game was piqued by the top-tier North American Soccer League, which featured megastars such as Pelé, Franz Beckenbauer, Carlos Alberto and Johan Cruyff.

“The speed with which everything happened was truly unique,” says Marsh, who ended his professional playing career three seasons earlier by leading the Tampa Bay Rowdies to back-to-back NASL Soccer Bowl championship games.

“We went into Charlotte cold, around six months before our first campaign, with no soccer activity in the city besides youth programs.”

In order to put together a roster, Marsh and his technical team held open tryouts, which attracted an intriguing cast of characters.

“All sorts of people turned up, including some who came wearing army-style boots! They just wanted to play soccer!” laughs Marsh. “We ended up putting together a team that was like the Dirty Dozen of soccer. It was outrageous.”

Those tryouts helped form the core of a roster that would make history. However, the star of the Championship-winning team, who became a local hero and league MVP, didn’t actually make the cut.

Cuba-born Tony Suarez played soccer at Myers Park High School, Appalachian State University and Belmont Abbey College, before taking his shot at turning professional with the Lightnin’.

“At tryouts, Tony’s attitude and enthusiasm were fantastic, but he came up short on everything we did,” recalls Marsh. “I had to cut him, but he asked if he could stay on and train as an amatuer. We had four roster spots for amateurs, so this wasn’t a problem. He was so keen to be involved that he offered to start driving the team bus! And he did! I couldn’t let him down.”

An injury crisis led to Suarez’s eventual start, and the fast-paced forward was an instant hit with local fans. In the Lightnin’s first season, Suarez ended up scoring 22 goals and was later named MVP in the 1981 ASL All-Star game held at Michigan’s Pontiac Silverdome.

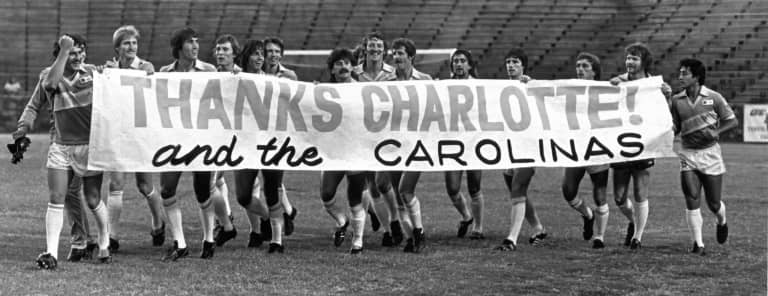

The Lightnin’ finished the 1981 regular season with a 28-9-3 record, and proceeded to secure playoff victories over the Rochester Flash and the Pennsylvania Stoners. That set up a single-match ASL Championship Final against New York United—who were, by coincidence, coached by Marsh the previous season.The match, on September 18, 1981, was supposed to be staged by New York United. However, their home Shea Stadium was unavailable, so the fixture was switched to the Queen City with just two weeks’ notice.

“In those two weeks, we set the goal of bringing in 10,000 fans to Memorial Stadium, and newspapers and local TV really got behind us,” says Marsh. “On the night, we only opened four turnstiles…. but suddenly we saw a lot more fans coming towards the stadium!”

Against all expectation, a total of 20,163 fans came to Memorial Stadium that night to witness a seminal moment in Carolina soccer history.

The Lightnin’ went 1-0 down shortly after the hour mark, before Irish midfielder Don Tobin’s equalizer forced two 20-minute periods of extra time.

With just three minutes to go before a penalty shootout, a Tobin corner fell to rookie defender David Pierce, who set up the winning header for New Jersey native Hugh O’Neill.

“We worked on that corner set piece all year long, from the very first day of practice, and then it won us the Championship at the very last moment!” says Marsh.

“You really couldn’t make it up. It was such a wild night.”

The Lightnin’ were an instant hit on the field—and the marketing nous of visionary owner Bob Benson and his team made sure they were a success off the field, too.Along with General Manager Rich Melvin and Director of Operations Ed Young, Benson was able to create enough buzz to bring in a total of 110,213 fans over the course of the 18-game season. The match average of 6,123 was a league record.

“The attendances surprised me, but the average crowd was so high because we had so many fantastic promotions,” says Marsh.

For one game, a local Chevrolet dealer lined up four brand-new Z-28 sports cars on the field. Any fans who could fly their plane into one of the sunroofs would earn themselves a new set of keys. Over 10,000 paper airplanes landed on the field, requiring an almighty cleanup job before play could resume. A 15-year-old girl from Concord went home with a new car.On another night, a Piper Tomahawk airplane was parked on the field, which would be given to the fan who was able to throw a plastic frisbee closest to its propeller. “That one got us days and days of publicity,” says Marsh, who brought attention to the franchise in his own right due to a nationwide beer commercial that regularly played as the team was starting up.

Another regular giveaway would see a Volvo parked on the field at halftime, and fans would attempt to kick a soccer ball into its sunroof. No one managed to win the Swedish car, but when testing out the publicity stunt in advance for insurance purposes, Marsh put his effort straight into the sunroof upon his first try. “That shot made the insurance premium for the giveaway shoot right up!” laughs Marsh.

Marsh, who also shared General Manager duties, came up with the idea of staging a Beach Boys concert straight after a game in June 1981. Over 16,000 fans watched the Lightnin’ beat the Dallas Americans 3-1 before enjoying some Good Vibrations from the Wilsons, on a stage that was set up and ready around 10 minutes after the final whistle.

“We ran so many brilliant promotions,” says Marsh. “We had ‘Burn Your Mortgage’ night and Harris Teeter ran an ‘All You Can Eat For a Year’ contest. Virtually every week, we had something happening. It was all down to Bob Benson, who had these wild and crazy ideas. I would put 90 percent of the success of the franchise on Bob and his vision.”

The airplane giveaways and post-match rock concerts might not have been the most absurd thing to happen on the Lightnin’s field of play. During a 1982 match against the Georgia Generals, goalkeeper Scott Manning was struck by lightning when his aluminum studs connected with a sprinkler head. Thankfully, the shot stopper was helped off the field without serious injury, and the game was duly abandoned.

Incredibly, this was the second time in Manning’s career that he had been hit by lightning, as the same fate befell him during a practice match a few years earlier. Lightning, it seems, can strike twice.

Despite the association with inclement weather, the team was able to attract one of the world’s greatest soccer stars to the roster for the 1983 campaign. Iconic English defender Bobby Moore, once described by German legend Franz Beckenbauer as “the greatest defender in the history of the game,” played alongside Marsh at Fulham. Moore captained England to World Cup victory 15 years before he came to Charlotte as an assistant coach.

“Everyone in the ‘football family’ knew who he was, but many others had no idea,” recalls Marsh. “But he absolutely loved his time in Charlotte.”Injuries on the team meant that a 42-year-old Moore stepped in to play eight games for the Lightnin’ in central defense.

“Carolina had so many injuries they activated Bobby Moore to play that night against us,” reminisced former Pennsylvania Stoners player Glenn Davis in a 2012 interview. “I remember we had a 2-0 lead and we absolutely crumbled in the final 10 minutes, with their fans going nuts. We totally collapsed as a team and lost 3-2. I think a lot of us were just in shock that Bobby Moore was playing that night.”

The Lightnin’s story was ultimately short-lived as the bubble burst on American professional soccer in the early 1980s. The American Soccer League folded in 1983, followed by the top-tier NASL in 1984. And with that, the Carolina Lightnin’ were consigned to the history books.

“I had such a brilliant three years in Charlotte,” says Marsh. “One thing that immediately struck me was how wonderful the people of North and South Carolina were. It was one of the happiest periods of my life.

“I’ve been following Charlotte since I left, and it has become a truly fantastic pro sports town.”

Perhaps the Queen City’s status in American sports, and its future as a force in Major League Soccer, owes a debt to the team that once took the town by storm.